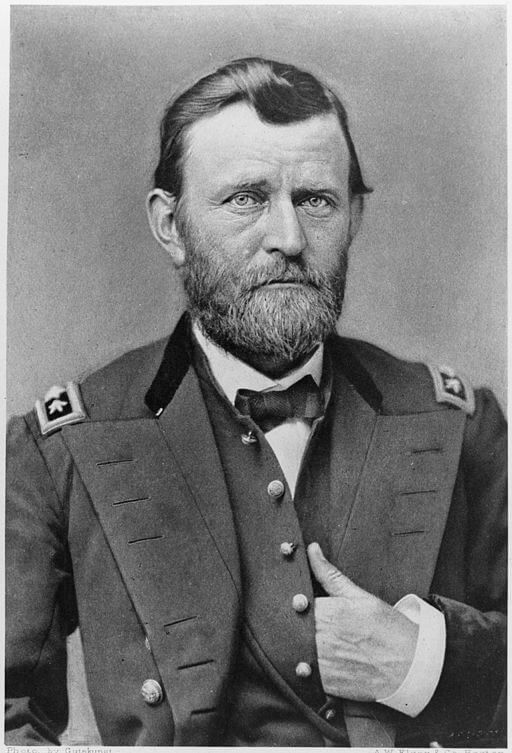

Ulysses S. Grant: A Child's Biography

This biography of Ulysses S. Grant for young children was excerpted from Mary Stoyell Stimpson's book, A Child's Book of American Biography (1915). Add over one hundred years to Ms. Stimpson's time reference when you read it with your children. You might also enjoy reading Robert E. Lee: A Child's Biography.

______________Once upon a time, at Point Pleasant, a small town on the Ohio River, there lived a young couple who could not decide how to name their first baby. He was a darling child, and as the weeks went by, and he grew prettier every minute, it was harder and harder to think of a name good enough for him.

Finally Jesse Grant, the father, told his wife, Hannah, he thought it would be a good plan to ask the grandparents' advice. So off they rode from their little cottage, carrying the baby with them.

But at grandpa's it was even worse. In that house there were four people besides themselves to suit. At last, the father, mother, grandfather, grandmother, and the two aunts each wrote a favorite name on a bit of paper. These slips of paper were all put into grandpa's tall, silk hat which was placed on the spindle-legged table. "Now," said the father to one of the aunts, "draw from the hat a slip of paper, and whatever name is written on that slip shall be the name of my son."

The slip she drew had the name "Ulysses" on it.

"Well," murmured the grandfather, "our dear child is named for a great soldier of the olden days. But I wanted him to be called Hiram, who was a good king in Bible times."

Then Hannah Grant, who could not bear to have him disappointed, answered: "Let him have both names!" So the baby was christened Hiram Ulysses Grant.

While Ulysses was still a baby, his parents moved to Georgetown, Ohio. There his father built a nice, new, brick house and managed a big farm, besides his regular work of tanning leather. As Ulysses got old enough to help at any kind of work, it was plain he would never be a tanner. He hated the smell of leather. But he was perfectly happy on the farm. He liked best of all to be around the horses, and before he was six years old he rode horseback as well as any man in Georgetown. When he was seven, it was part of his work to drive the span of horses in a heavy team that carried the cord-wood from the wood-lot to the house and shop. He must have been a strong boy, for at the age of eleven he used to hold the plow when his father wanted to break up new land, and it makes the arms and back ache to hold a heavy plow! He was patient with all animals and knew just how to manage them. His father and all the neighbors had Ulysses break their colts.

In the winters Ulysses went to school, but he did not care for it as much as he did for outdoor life and work with his hands. Still he usually had his lessons and was decidedly bright in arithmetic. Because he was not a shirk and always told the truth, his father was in the habit of saying, after the farm chores were done: "Now, Ulysses, you can take the horse and carriage and go where you like. I know I can trust you."

When he was only twelve, his father began sending him seventy or eighty miles away from home, on business errands. These trips would take him two days. Sometimes he went alone, and sometimes he took one of his chums with him. Talking so much with grown men gave him an old manner, and as his judgment was pretty good he was called by merchants a "sharp one." He would have been contented to jaunt about the country, trading and colt-breaking, all his life, but his father decided he ought to have military training and obtained for him an appointment at West Point (the United States' school for training soldiers that was started by George Washington) without Ulysses knowing a thing about it. Now Ulysses did not have the least desire to be a soldier and did not want to go to this school one bit, but he had always obeyed his father, and started on a fifteen days' journey from Ohio without any more talk than the simple statement: "I don't want to go, but if you say so, I suppose I must."

He found, when he reached the school, that his name had been changed. Up to this time his initials had spelled HUG, but[66] the senator who sent young Grant's appointment papers to Washington had forgotten Ulysses' middle name. He wrote his full name as Ulysses Simpson Grant, and as it would make much trouble to have it changed at Congress, Ulysses let it stand that way. So instead of being called H-U-G Grant (as he had been by his mates at home) the West Point boys, to tease him, caught up the new initials and shouted "Uncle Sam" Grant, or "United States" Grant—and sometimes "Useless" Grant.

But the Ohio boy was good-natured and only laughed at them. He was a cool, slow-moving chap, well-behaved, and was never known to say a profane word in his life. At this school there was plenty of chance to prove his skill with horses. Ulysses was never happier than when he started off for the riding-hall with his spurs clanking on the ground and his great cavalry sword dangling by his side. Once, mounted on a big sorrel horse, and before a visiting "Board of Directors," he made the highest jump that had ever been known at West Point. He was as modest as could be about this jump, but the other cadets (as the pupils were called) bragged about it till they were hoarse.

After his graduation, Grant, with his regiment, was sent to the Mexican border. In the battle of Palo Alto he had his first taste of war. Being truthful, he confessed afterwards that when he heard the booming of the big guns, he was frightened almost to pieces. But he had never been known to shirk, and he not only rode into the powder and smoke that day, but for two years proved so brave and calm in danger that he was promoted several times. But he did not like fighting. He was sure of that.

At the end of the Mexican War, Ulysses married a girl from St. Louis, named Julia Dent, and she went to live, as soldiers' wives do, in whatever military post to which he happened to be sent. First the regiment was stationed at Lake Ontario, then at Detroit, and then, dear me! it was ordered to California!

There were no railroads in those days. People had to go three thousand miles on horseback or in slow, lumbering wagons. This took months and was both tiresome and dangerous. Every little while there would be a deep river to ford, or some wicked Indians skulking round, or a wild beast threatening. The officers decided to take their regiments to California by water. This would be a hard trip but a safer one.

It was lucky that Mrs. Grant and the babies stayed behind with the grandparents, for besides the weariness of the long journey, there was scarcity of food; a terrible cholera plague broke out, and Ulysses Grant worked night and day. He had to keep his soldiers fed, watch out for the Indians, and nurse the sick people.

Well, after eleven years of army life, Grant decided to resign from the service. He thought war was cruel; he wanted to be with his wife and children; and a soldier got such small pay that he wondered how he was ever going to be able to educate the children. Farming would be better than fighting, he said.

He was welcomed home with great joy.[69] His wife owned a bit of land, and Grant built a log cabin on it. He planted crops, cut wood, kept horses and cows, and worked from sunrise till dark. But the land was so poor that he named the place Hardscrabble. Even with no money and hard work, the Grants were happy until the climate gave Ulysses a fever; then they left Missouri country life and moved into the city of St. Louis.

In this city Grant tried his hand at selling houses, laying out streets, and working in the custom-house; but something went wrong in every place he got. He had to move into poorer houses, he had to borrow money, and finally he walked the streets trying to find some new kind of work. Nobody would hire him. The men said he was a failure. Friends of the Dent family shook their heads as they whispered: "Poor Julia, she didn't get much of a husband, did she?"

Then he went back to Galena, Illinois, and was a clerk in his brother's store, earning about what any fifteen-year-old boy gets to-day. He worked quietly in the store all day, stayed at home evenings, and was called a very "commonplace man." He was bitterly discouraged, I tell you, that he could not get ahead in the world. And his father's pride was hurt to think that his son who had appeared so smart at twelve could not, as a grown man, take care of his own family. But Julia Dent Grant was sweet and kind. She kept telling him that he would have better luck pretty soon.

In 1861 the Americans began to quarrel among themselves. Several of the States grew very bitter against each other and were so stubborn that the President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, said he must have seventy-five thousand men to help him stop such rebellion. Ulysses Grant came forward, and said he would be one of these seventy-five thousand, and enlisted again in the United States Army. He was asked to be the colonel of an Illinois regiment by the governor of that State. Then, you may be sure, what he had learned at West Point came into good play. He soon showed that he knew just how to train men into fine soldiers. He did so well that he was made Brigadier-general.

He stormed right through the enemies' lines and took fort after fort. Oh, his work was splendid—this man who had been called a failure!

A general who was fighting against him began to get frightened, and by and by he sent Grant a note saying: "What terms will you make with us if we will give in just a little and do partly as you want us to?"

Grant laughed when he read the letter and wrote back: "No terms at all but unconditional surrender!" Finally the other general did surrender, and when the story of the two letters and the victory for Grant was told, the initials of his name were twisted into another phrase; he was called Unconditional Surrender Grant. This saying was quoted for months, every time his name was mentioned. At the end of that time, he had said something else that pleased the people and the President.

You see, the war kept raging harder and harder. It seemed as if it would never end. Grant was always at the front of his troops, watching everything the enemy did and planned, but he grew sadder and sadder. He felt sure there would be fighting until dear, brave Robert E. Lee, the southern general, laid down his sword. The whole country was sad and anxious. They said: "It is time there was a change—what in the world is Grant going to do?" And he answered: "I am going to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer!" No one doubted he would keep his word. It did take all summer and all winter, too. Then, when poor General Lee saw that his men were completely trapped, and that they would starve if he did not give in, he yielded. Grant showed how much of a gentleman he was by his treatment of the general and soldiers he had conquered. There was no lack of courtesy toward them, I can tell you. When the cruel war was ended, Grant was the nation's hero.

Later, Grant was made President of the United States he had saved. When he had finished his term of four years, he was chosen for President again. After that he traveled round the world. I cannot begin to tell you the number of presents he received or describe one half the honors which were paid him—paid to this man who, at one time, could not get a day's work in St. Louis. This farmer from Hardscrabble dined with kings and queens, talked with the Pope of Rome, called on the Czar of Russia, visited the Mikado of Japan in his royal palace, and was given four beautiful homes of his own by rich Americans. One house was in Galena, one in Philadelphia, one in Washington, and another in New York. New York was his favorite city, and in a square named for him you can see a statue showing General Grant on his pet horse, in army uniform. On Claremont Heights where it can be seen from the city, the harbor, and the Hudson River, stands a magnificent tomb, the resting-place of the great hero who was born in the tiny house at Point Pleasant.

There was always a good deal of fighting blood in the Grants. The sixth or seventh great-grandfather of Ulysses, Matthew Grant, came to Massachusetts in 1630, almost three hundred years ago; over in Scotland, where he was born, he belonged to the clan whose motto was "Stand Fast." I think that old Scotchman and all the other ancestors would agree with us that the boy from Ohio stood fast. And how well the name suited him which his aunt drew from the old silk hat—Ulysses—a brave soldier of the olden time!

Ulysses S. Grant's story is featured in our collection, American Biographies for Kids. You may also enjoy visiting American History for more authors and their writings which helped shape the country.

Return to the Ulysses S. Grant page

Return to the American History home page