Thomas Jefferson: Why Some Succeed

This biography of Thomas Jefferson was written by H.A. Lewis in his book, "Hidden Treasures: Why Some Succeed While Others Fail" (1887). Lewis writes: "It was while a student that he heard the famous speech of Patrick Henry; and those immortal words, "give me liberty or give me death," seemed to kindle within him a patriotic spirit which grew until it burst forth in that noble statue to his memory,—the Declaration of Independence, which was the work of his pen."

The subject of this narrative was born in Virginia, in the year 1743, on the 2nd day of April. As young Jefferson was born to affluence and was bountifully blessed with all the educational advantages which wealth will bring, many of our young readers may say—well, I could succeed, perhaps, had I those advantages. We will grant that you could provided you took means similar to those used by Jefferson, for while we must admit that all cannot be Jeffersons, nor Lincolns, nor Garfields, still we are constantly repeating in our mind the words of the poet:—

The subject of this narrative was born in Virginia, in the year 1743, on the 2nd day of April. As young Jefferson was born to affluence and was bountifully blessed with all the educational advantages which wealth will bring, many of our young readers may say—well, I could succeed, perhaps, had I those advantages. We will grant that you could provided you took means similar to those used by Jefferson, for while we must admit that all cannot be Jeffersons, nor Lincolns, nor Garfields, still we are constantly repeating in our mind the words of the poet:—

"Lives of great men all remind us We can make our lives sublime, And, departing, leave behind us Footprints on the sands of time,"

it has been said that where twenty enter the dry-goods trade nineteen will fail and from their despair behold the odd one succeed—utilizing the very weapons within their own grasp to bring about his success. This is true, not only of the dry-goods trade but of all trades, of all professions, and to resume our subject—Jefferson had much with which to contend.

He finally attended school at William and Mary College for two years. Here he strove to cultivate friendly feelings with all whom he met, with excellent success, becoming very popular with both companions and teachers. It was while a student that he heard the famous speech of Patrick Henry; and those immortal words, "give me liberty or give me death," seemed to kindle within him a patriotic spirit which grew until it burst forth in that noble statue to his memory,—the Declaration of Independence, which was the work of his pen. He studied law for a time, after a two years' college course, when, in 1767 he began its practice.

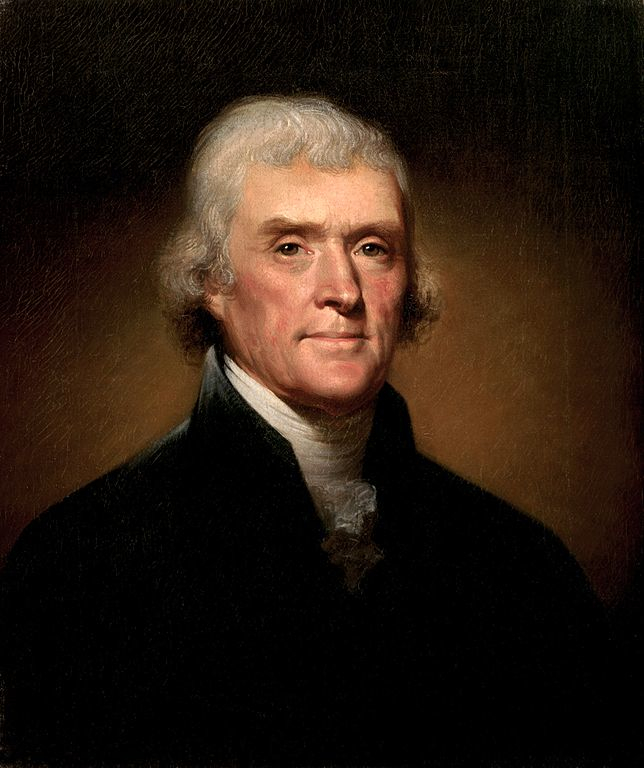

As Mr. Jefferson is described as tall and spare with gray eyes and red hair, surely his success is not due to his personal appearance. At the beginning of his practice he was not considered what might be termed brilliant, but the fact that he was employed on over two hundred cases within the first two years of his practice proves the secret of his success to have been his undefatigable energy. It is also stated that he rarely spoke in public which shows his good sense in discovering where his strength lay,—then pushing on that line to success.

He was elected by his countrymen to the house of Burgesses where he at once took a decided stand against parliamentary encroachment. It was in this first of his legislative efforts that he brought forward a bill tending[168] to the freedom of slaves, provided their masters felt so disposed, but this measure was defeated. The house of Burgesses appointed him a member of the committee of correspondence. The duty of this committee was to disseminate intelligence upon the issues of the day, notably the system of taxation which the mother-country was trying to impose upon the colonies.

His article entitled: "A Summary View of the Rights of British America," was a masterly production, clearly defining the right of the colonies to resist taxation, and it was the principles here set forth that were afterwards adopted as the Declaration of Independence. This, paper was printed, not only in America, but in England, where its author was placed on the roll of treason and brought before parliament. This document also placed Jefferson in America among the foremost writers of that age; it also showed him to be a bold and uncompromising opponent of oppression, and an eloquent advocate of constitutional freedom.

He was sent to the Continental Congress. On the floor he was silent but he had the 'reputation of a masterly pen,' says John Adams, and in committee was a most influential member. He drafted the Declaration of Independence, and on June 28th it was laid before Congress and finally adopted, with but a few verbal changes. This document probably has the greatest celebrity of any paper of like nature in existence.

He now resigned his seat in Congress to push needed reform in his State preparatory to the new order of affairs. The first thing needed was a State constitution. Jefferson aided much in the framing of this. He was placed on the committee to reorganize the State laws, and to Jefferson is due the abolition of[169] Primogenitureship—the exclusive right of the first-born to all property of the family. The measure establishing religious freedom, whereby people were not to be taxed for the support of a religion not theirs, was also the work of his hand. These measures were very democratic indeed and owing to the aristocratic views of the people at that time, excited great opposition, but they were finally passed and since have been law.

Thus it will be seen that Jefferson was the author of many of our dearest ideas of equality. In 1778 he procured the passage of a bill forbidding future importation of slaves and the next year he was elected governor of Virginia, to succeed Patrick Henry. He assumed the duties of this office in a most gloomy time. The enemy were preparing to carry the war into the South, and Jefferson knew they would find Virginia almost defenseless. Her resources were drained to the dregs to sustain hostilities in South Carolina and Georgia, and her sea coast was almost wholly unprotected. The State was invaded by the enemy several times and once the Governor was almost captured by Tarleton.

Jefferson declined a re-election as he perceived that a military leader was needed, and he was succeeded by General Nelson. Jefferson was appointed one of the Ministers of the Colonies to Europe to assist Adams and Franklin in negotiating treaties of commerce. He was the means which brought about our system of coins, doing away with the old English pounds, shillings and pence, substituting the dollar and fractions of a dollar, even down to a cent. He became our Minister to France in 1785 in place of Franklin who had resigned. Here he did good service for his country by securing the admission [170]into France of tobacco, flour, rice and various other American products.

Being offered the head of Washington's cabinet, he accepted it. Immediately upon his entrance into the cabinet, in 1790, began the struggle between the Federalist and Republican parties, their leaders, Hamilton and now Jefferson, both being members of the cabinet. Jefferson was probably the real originator of the State sovereignity idea, and the constitution did not wholly meet his approval. He thought better of it, however, when he became President and felt more forcibly the need of authority in such a trying position.

He had just returned from an extended trip through Europe, and he contended that the world was governed too much. He was intensely Democratic in his belief and as the head of the then rising Republican party—now the Democratic—opposed all measures which tended toward centralizing in one government, characterizing all such measures as leading to monarchy.

Washington was a Federalist, and in all the leading measures gave his support to Mr. Hamilton, Mr. Jefferson's opponent. As it was out of the question for Jefferson to remain in the cabinet of an executive wholly at variance with him politically, he accordingly resigned in 1793 and retired to his farm at 'Monticello' to attend to his private affairs as he was embarrassed financially at this time, and his attention was very much needed.

In 1796, Washington designing to retire from public service, the two great parties decided upon Adams and Jefferson as their standard-bearers; the electoral votes being counted, it was found that Adams stood first and Jefferson next. Adams was therefore declared president and Jefferson, according to existing law, vice-president.[171] Then followed the alien and sedition laws and the war demonstrations against France by the federal party, which was objected to by the Republicans. The bearing of France became so unendurable that Washington offered to take his place at the head of the army. Finding all else of no avail, the Republicans resorted to the State Arenas; the result was the 'Kentucky and Virginia resolutions of '98,' the former of which was the work of Jefferson, the latter that of Madison. As is well known these were the foundation, years after, of Calhoun's Nullification Views. It was a principle of Jefferson, which was never effectually settled, until civil war had rent the nation almost in twain.

Happily peace triumphed, and in the campaign that followed, the Republicans were successful, Mr. Jefferson becoming president—Aaron Burr vice-president. Jefferson's ascension to the presidency caused a complete revolution in the politics of the country. The central idea around which the party revolved was the diffusion of power among the people. To this idea they would bend every question indiscriminately, whether it related to a national bank, tariff, slavery, or taxes. It held that in the States themselves rested the original authority, that in the government lay the power only for acts of a general character. Jefferson, their first president, now came to Washington.

President Washington came to the capitol with servants in livery, in a magnificent carriage drawn by four cream-colored horses, Jefferson came on horseback, hitching his horse to a post while he delivered a fifteen minute address. He abolished the presidential levees, and concealed his birthday to prevent its being celebrated. He even detested the word minister prefixed to one's name, and eschewed breeches, wearing pantaloons.[172] It was during his administration that Louisiana was purchased, although, according to his own theory, he had no constitutional right to do so, but the great benefit derived from this purchase soon silenced all opposition.

It was during his administration that the piratical Barbary States were cured of their insolence, and in his second term that Burr's trial occurred. At the close of this second term he retired to private life to become the 'Sage of Monticello.' He now turned his attention to the establishing of the University of Virginia. He was a believer in the free development of the human powers so far as was consistent with good government. He subjected the constitution of the United States to a careful scrutiny governed by this theory, and became convinced that the doctrine of State sovereignty was right and he fought for it persistently when called to the head of the government.

His inaugural address breathed that idea, but when Aaron Burr bearded the authority of his government he began to realize the rottenness of such a foundation, and when it came to the purchase of Louisiana, his doctrine had to be stretched, and he finally became convinced, as he expressed it, that the Government must show its teeth.

On July 4th, 1826, at a little past noon, he died, a few hours before his political opponent, but fast friend, John Adams. How strange to think that about that hour fifty years before they had each signed the declaration of the freedom of the country which they had so ably served. The granite for his monument lies unquarried nor is its erection needed. The Declaration of Independence is a far greater monument than could be fashioned from brass or stone.

You might also be interested in reading H.A. Lewis' biography about Alexander Hamilton's Duel with Aaron Burr in which the author compares skills and contributions by both Jefferson and Hamilton. Enjoy finding out about other important figures and their writings in our collection American History.

Return to the Thomas Jefferson page

Return to the American History home page